Adventures of an ALMOST fifty-year-old backpacker chronicles my six-month journey through New Zealand, Australia, SE and E Asia. You can read the origin story here.

It’s got culture, history, travel advice, and just a sprinkle of neuroses.

It’s free, so you should subscribe, share with family and friends, and leave your thoughts and recommendations in the comments.

From a Da Nang to Dong Hoi train, I peered out onto one of Vietnam’s most scenic stretches. Hills jut into the sea, creating inlet after inlet. Viny bushes with white trumpet flowers cover the ground, looking like a million morning glories undulating to the beach below. As we approached a tunnel, the sky was blue. As we exited, and the train barreled into a mist, my thoughts turned inward.

In a couple of days, Curtis and I would embark on a four-day trek to and through Son Doong Cave. It’s the world’s largest, but I wasn’t sure how. Is it the longest? The tallest? I figured as with any cave, I’d confront tight spaces, and that was making me a little anxious. When I registered for the trek a year prior (because that’s how far in advance one needs to register to secure a spot), tight spaces hadn’t crossed my mind. But the previous week I’d experienced what might have been my first minor bought of claustrophobia.

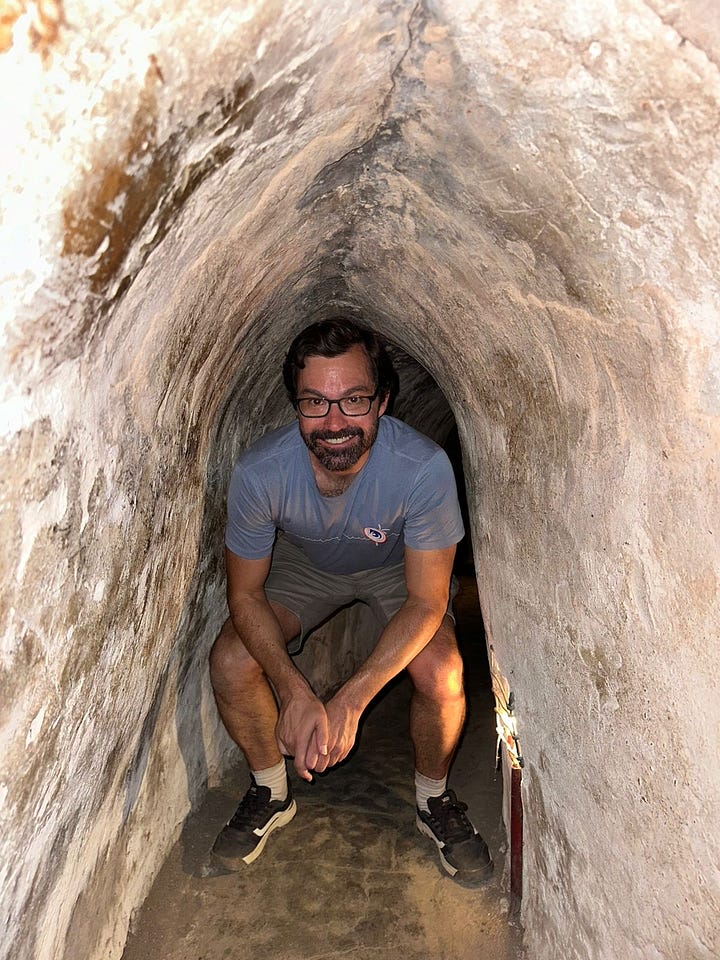

I was in Cu Chi, outside of Saigon, where the Vietnamese built a vast network of tunnels during the war to protect villagers from bombardment and as a tool for guerrilla warfare. Most of the tour takes place above ground, but to get a sense of what it was like down there, visitors can crawl through a 330-foot portion of a 25-inch-wide tunnel. As I entered the tunnel on my hands and knees, with several people behind me, my chest tightened. I felt I couldn’t breathe. I turned my head to tell Curtis he needed to back out, which he did, and then I backed out. Once I resurfaced, I pulled myself together, and crawled through a 100-foot portion instead. My perseverance gave me peace of mind, but what if I have a similar reaction in Son Doong cave?

The following afternoon, after a chill twenty-four hours spent mostly in our Dong Hoi hotel room, a couple of guys from Oxalis Adventures, the exclusive tour company for the Son Doong trek, picked us up and brought us to a hotel in Phong Na.

At that evening’s safety briefing, where I learned I’d need to watch out for snakes and leeches, I met our eight trekking companions. Four women and four men. 29 to 61. Four live in the US, although only two were born there. One is Canadian, one Korean, one Thai, and one European, although he claimed to be enjoying his eleventh year “homeless.”

Dat was our English-speaking guide. A young guy from Hanoi, he was wonderfully sarcastic and made us feel supported and comfortable. Adam, a British caver and an original explorer of Son Doong Cave in the early 2000s, served as our safety specialist. Six safety assistants, two cooks, and seventeen porters also accompanied us. They were quite the crew, managing a seamless operation (at least for the things that they could control).

Day 1

A lux bus carried us into Phong Nha - Ke Bang National Park, which is home to hundreds of miles of jungly mounds and rivers. We drove along the thin and windy Ho Chi Min trail, built during the war as the primary Vietnamese north to south supply route. Dat pointed out a bald cliff side bombed by Americans during the war, a reminder that even here, in remote Vietnam, the legacy of war remains.

Our hike began as a steep descent through the jungle. A layer of sweat immediately enveloped me and I felt pressure on my left knee.

Guess there’s no easing into this.

Ninety minutes later, we crossed our first river, and while I’d been warned that my shoes would be wet for the next four days, which was another thing that made me a bit uneasy, submerging my feet cooled my body. As we exited one crossing, I looked forward to the next, and fortunately we crossed several more before lunch.

After lunch we trekked a few more hours, up and down hills, in dense jungle, through dry and not so dry riverbeds, until I spotted a cave opening in the distance. I asked Dat if it was Son Doong. “No, it’s Hang En,” he said. “It’s where we’ll be spending the night. We don’t arrive to Son Doong until tomorrow.”

NOTE: The Oxalis website is one of the most comprehensive I’ve ever seen. It explains what makes Son Doong the largest cave. It details every aspect of our itinerary, including that we’d be sleeping in Hang En cave the first night. I guess I hadn’t read much more than the packing list, which is unlike me, but I think that was a good thing because despite my stupid questions, the adventure unfolded before me.

As we entered the mouth of Hang En cave, Dat asked us to take out your helmets so the safety assistants could fit us with lights. We then ducked through a thin entranceway, which I’m happy to report didn’t feel claustrophobic, but also didn’t go on for very long.

Once through, I stood in the most massive cavern I’d ever seen. It could literally hold more than five domed football stadiums. And this was not even Son Doong. I began to understand what world’s largest meant, and I was awestruck.

From a cliff’s edge, inside the cave, I saw our campsite down below. Across a river sat a collection of already constructed tents, bathrooms, a kitchen, and an eating area. We scrambled down a steep descent, took a small raft across the river, settled into our assigned tents, and returned to the river in our bathing suits for one of the more refreshing swims in history.

After a delicious, mostly-Vietnamese dinner (plus French fries), in this massive cave, with a shaft a light coming down from a hole that is rimmed with trees, with all my needs taken care of, I went to sleep feeling like one of the luckiest people on earth. Jackpot.

Day 2

I awoke to a cool breeze accompanied by a sunbeam reflecting off the river. As I removed my earplugs, the tweets of a thousand birds replaced my breath. They’d come at night and would venture out that morning. I sneezed and heard it echo through the cave. Sorry. I picked up my phone to check the time. 5:30 AM. Without a phone signal I couldn’t scroll, so I spent the next hour looking up at the mouth of the cave, watching for subtle changes in light.

Later than morning, as I cut into my eggs, I heard an unmistakably Eastern European accent declare, “It was coming out both ends.” Sorina then sat down on a small stool, staring blankly. Her friend Anita, with whom she’d traveled from Colorado, lovingly asked if she’d like to proceed or go back. Neither option was good, considering the distance and terrain, so Sorina chose forward. Sorina seems like the type who usually chooses forward.

After packing our bags for the porters to carry to the next campsite, we trekked a short distance to the other side of cave. The exit was a massive arch through which the silhouettes of a hundred fluttering birds obscured tiny portions of a green mountain backdrop.

Just outside the exit, a shallow river flowed by.

“I just want to lie in the river,” Sorina said.

“Do it,” Anita replied.

Next thing I know, Sorina is on her back, in the river, with Anita cupping water over her head. It’s what I imagine a baptism is like, and in some ways, we were all hoping that Sorina would feel reborn.

To get to Son Doong cave we followed the river through a thin valley, crossing it several times. Thousands of butterflies fluttered along its banks. I heard thunder, which according to Dat came from Laos, on the other side of mountains. Despite it being dry season in Vietnam, it was rainy season in Laos. I guess we were close enough, because a few drops reached us as we ascended out of the valley, protected by a canopy of trees.

Near the mouth of Son Dong we stopped for lunch. I looked over at Sorina, and could see life returning to her eyes. She wasn’t 100%, but improving. Hallelujah!

It was time to enter Son Doong. The safety team rigged us up with harnesses and carabiners, because apparently, we’d be repelling into the cave. Fun!?

This cave was the real deal. It was not at all hospitable. It was very dark, except when I’d turned to view the hole from which we entered. Bugs and bats swarmed as we stopped to admire huge stalagmites and slowly cross rivers.

In the afternoon sometime, because what’s time in a cave, we reached our campsite nestled under Doline 1. A Doline is formed when a portion of the cave’s roof collapses, letting in natural light. Doline 1, which sat 1400 feet above our heads, was likely created over a million years ago. The chance of more collapse while we were in there, I was assured, because of course I asked, was very slim.

We proceeded to drop our day packs at our tents, keep on all our clothes, don life vests, and plunge into a cold, dark underground river. Once my heart restarted, I felt my muscles relax. We swam back, dried off, ate a tasty dinner, and then sat around a charcoal grill, eating freshly grilled sweet potatoes, discussing the day.

As I drifted off to sleep, I thought how crazy it is that for the next thirty-six hours I’d be in a cave. If it would be anything like the first few hours, it would be beyond epic. What I didn’t know, in my blissful ignorance, was that it would be far more challenging than I’d imagined.

End part 1

The ALMOST-fifty backpacker’s Hotlist

There are innumerable places to try. We researched, solicited recommendations, and pursued a few. Below are the ones I recommend, although some come with caveats, so read the brief descriptions to get my take.

The Vietnam hotlist, consisting of Saigon, Hoi An, and Hanoi, will be published separately in a couple of weeks.

Notes:

All photos taken by Curtis Blessing or me.

If you’d like more detail on our exact itinerary, including museums, restaurants, etc, check out my Wanderlog guide, which I’ll publish in a couple of weeks with the hotlist.

I’ve put daily pics and video on Instagram, mostly in my stories, so follow me there for a day by day account.

Hit me up with thoughts or questions in the comments.

Wow, looks like an awesome adventure. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for sharing. I cannot wait for part 2!